In southeastern Ukraine lies the Zaporizhzhia nuclear power station.

Captured by Moscow soon after its 2022 invasion of Ukraine, the plant has frequently been caught in the crossfire, becoming a continual source of worry for international observers.

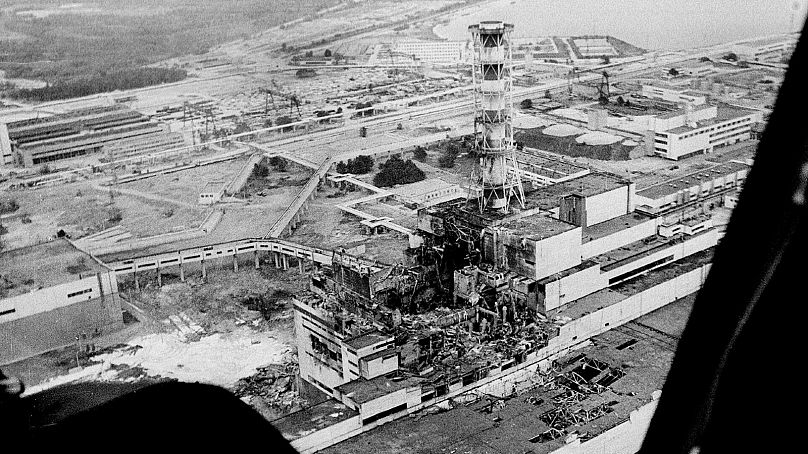

Some have even warned of nuclear disaster, similar to Chernobyl.

The latest concerning incident saw a drone hit the plant in April, with both sides exchanging blame.

Firing kamikaze drones at Zaporizhzhia is “a no-brainer”, former International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) chief nuclear inspector Robert E. Kelley tells Euronews.

He adds “there’s really no possibility whatsoever that these things” could cause the plant to explode, however.

The IAEA confirmed that it had not observed any structural damage after the last incident, on 7 April, although it strongly condemned the attack.

‘No chances’ of Chernobyl scenario today

Some previous strikes on Zaporizhzhia have resulted in power outages.

Technically, this is dangerous. Without power, nuclear reactors can’t be cooled down, overheat, and might explode – like at Chernobyl.

But chances this could happen today “are essentially zero”, says Kelley.

“Chernobyl’s reactor was suddenly turned to full power with all of this water in it, which turned to steam in a fraction of a second and just blew that building to pieces,” he explains.

“The reactors that are built today are built to a totally different standard. Chernobyl-type reactors include tons of flammable graphite to control the nuclear reaction while Zaporizhzhia’s pressurized water reactor (PWR) does not.”

“At Chernobyl, the graphite caught fire and spewed radioactive isotopes and ash into the atmosphere for days until the fire was put out. PWRs have no such flammability problem, a huge advantage. Water does not burn.”

“Also, Chernobyl’s reactor was inside a large ordinary industrial building that was destroyed by a steam explosion and a massive fire. PWR (except for a very few older Russian reactors) are always built inside a massive concrete and steel dome designed to contain a steam explosion and to slow down any leaks of radioactive isotopes to the environment.”

More factors seem to further reduce the risk compared to 1986.

During previous Zaporizhzhia blackouts, electricity supply could be diverted from other sources, such as the nearby Zaporizka Coal Fired Power Plant – Ukraine’s largest thermal power plant – and from diesel generators. This limits the chances of dangerous power outages.

Every Zaporizhzhia reactor is also currently in shutdown, unlike the Chernobyl one that was fully operational.

Despite Moscow’s takeover, the plant’s personnel largely stayed put, reducing the risk of it being mishandled.

“The Ukrainian citizens that were forced by the Russians to stay in Zaporizhzhia and run this plant for two years should be treated like heroes, and the IAEA could play a role in this,” adds Kelley.

“There’s a tendency to want to treat them as collaborators. I think they should get a medal for having served the country in a difficult position, they went through hell.”

Is Europe prepared for a nuclear disaster?

The short answer seems yes.

More than 150 reactors are operating across the EU’s 27 member states.

Each country has an agency for nuclear preparedness, even those that don’t have reactors.

“Coordination has increased a lot since the 2011 Fukushima disaster,” emergency preparedness specialist at the Swedish Radiation Safety Agency Jan Johansson tells Euronews.

Nuclear safety guidelines are usually established internationally by the IAEA.

In Europe, the organisation coordinating safety procedures across different countries is the HERCA, while the EMSREG is the EU body ensuring they are implemented in single states.

“HERCA has been quite active in terms of Ukraine, to try to harmonise and discuss what to do if there was a nuclear accident in Ukraine,” says Johansson.

What does a nuclear incident response plan look like?

“Preparation is the most important part,” Johansson explains.

“Whatever happens, even a meltdown, will take some time before it occurs. If something goes wrong, generally we know before the actual radiation leak.”

In the worst possible scenario – an explosion with radiation release – a five-kilometre-radius area around the incident (Precautionary Action Zone) gets evacuated.

Once the danger is detected, the entire population within a radius of 25 kilometres – the Urgent Protective Action Planning Zone – is alerted by alarms, sirens and a text message.

Alarms sound both on the street and in homes. Every house near a nuclear power plant, at least in Sweden, is equipped with a radio receiver that goes off in case of danger.

Everyone within 25 kilometres must shelter indoors. “A normal home should be fine, even in case of a large radioactive release,” says Johansson, as well as a school. There’s no need to stay in a bunker.

All citizens also have an iodine tablet which blocks radiation absorption by the thyroid gland, thus preventing thyroid cancer risks. Each household receives it, every five years. But whether it’s necessary to ingest it depends on the scale of the radiation leak.

Once people are sheltered, it is essential to turn on the television or the radio or to follow authorities on social media for live information.

In Sweden, local media too are trained to distribute this type of guidance.

“The next steps depend on the amount of radioactive material leaked, as well as on meteorological factors,” he says.

“We practice several times during the year. We believe we have a pretty effective system, and the authorities know what to do.”