When Willie Mays was perfecting his craft on the sandlots around Birmingham as a teenager in the 1940s, there was hardly anything bigger among the Black community than baseball. Overflowing crowds of Black fans packed Rickwood Field, the local ballpark, when the Birmingham Black Barons played, and on Sundays church would let out early so worshipers could watch baseball.

That is largely a bygone era.

“I don’t think they know anything about Black baseball as such,” said Charles Willis, 92, a high school teammate of Mays who played one season for the Black Barons, referring to Black children in Birmingham today. “Because nowadays, Black kids don’t play baseball.”

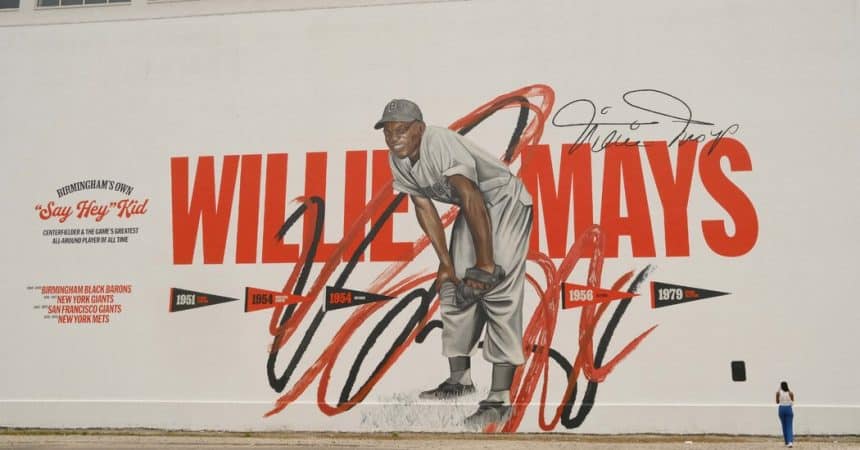

Major League Baseball went to Rickwood this week as a tribute to the history of the Negro leagues, a celebration that will now encompass a memorial service for Mays, who died on Tuesday at 93. The celebration, concluding on Thursday evening with a regular-season game between the San Francisco Giants and the St. Louis Cardinals, is largely about honoring the past. But it is also about looking ahead, wrestling with how to attract young African American athletes to play baseball at a time when African American representation in the sport has diminished.

“The biggest thing that excites me is that we are discussing baseball again in the Black community,” said Nelson George, a filmmaker who produced the 2022 documentary “Say Hey, Willie Mays!” “Because, let’s be frank, baseball has fallen out. The generation of Hank Aaron and Willie Mays and Bob Gibson, these were all-stars and the equivalent of Lebron — to any N.F.L. player.”

While still broadly popular, baseball has struggled in recent years to maintain its once tight grip on the national consciousness. As football and basketball have risen, baseball’s slower pace and reliance on nostalgia have threatened to make it seem less cool to younger American sports fans.

New York Times